USVI Corals Suffer Another Major Coral Bleaching Event

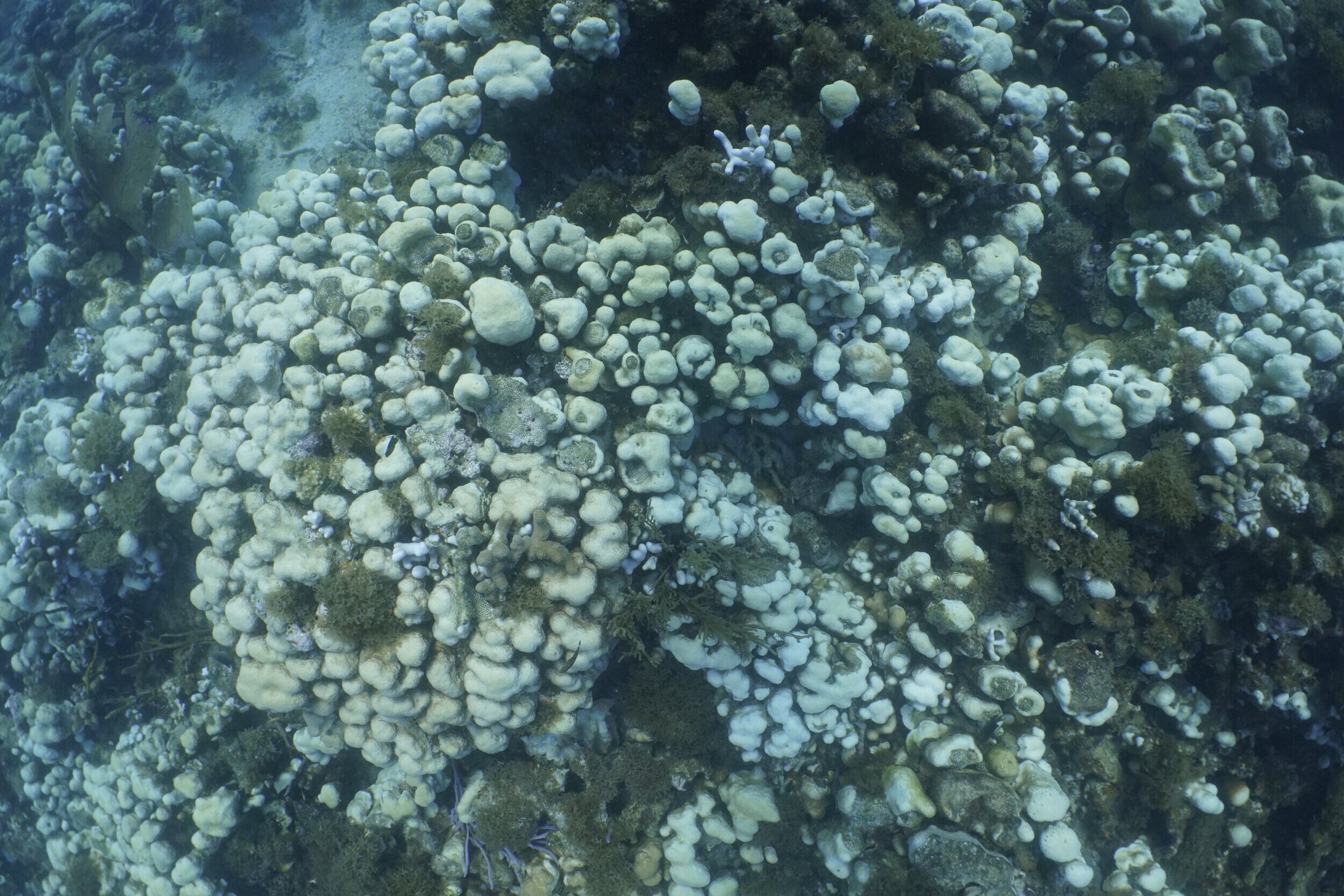

Already stressed coral reefs in the USVI have suffered through another coral bleaching event, surpassed only by the catastrophic 2005 bleaching event.

This coral reef at Brewers Bay Beach shows distinct signs of bleaching. Photo by Rosmin Ennis, October 29, 2019

In 2005 scientists at the University of the Virgin Islands measured unprecedented increases in ocean temperatures resulting in mass coral bleaching and mortality. At that time, approximately 60% of our shallow water corals bleached and died. Between August to October this year, increases in ocean temperatures nearly as severe as 2005 were measured; scientists expect to see dead and dying coral as a result. The problem is, even if a coral is able to survive bleaching from overly warm waters, its immune system is compromised and it becomes easy prey to coral diseases.

What Is Coral Bleaching Anyway?

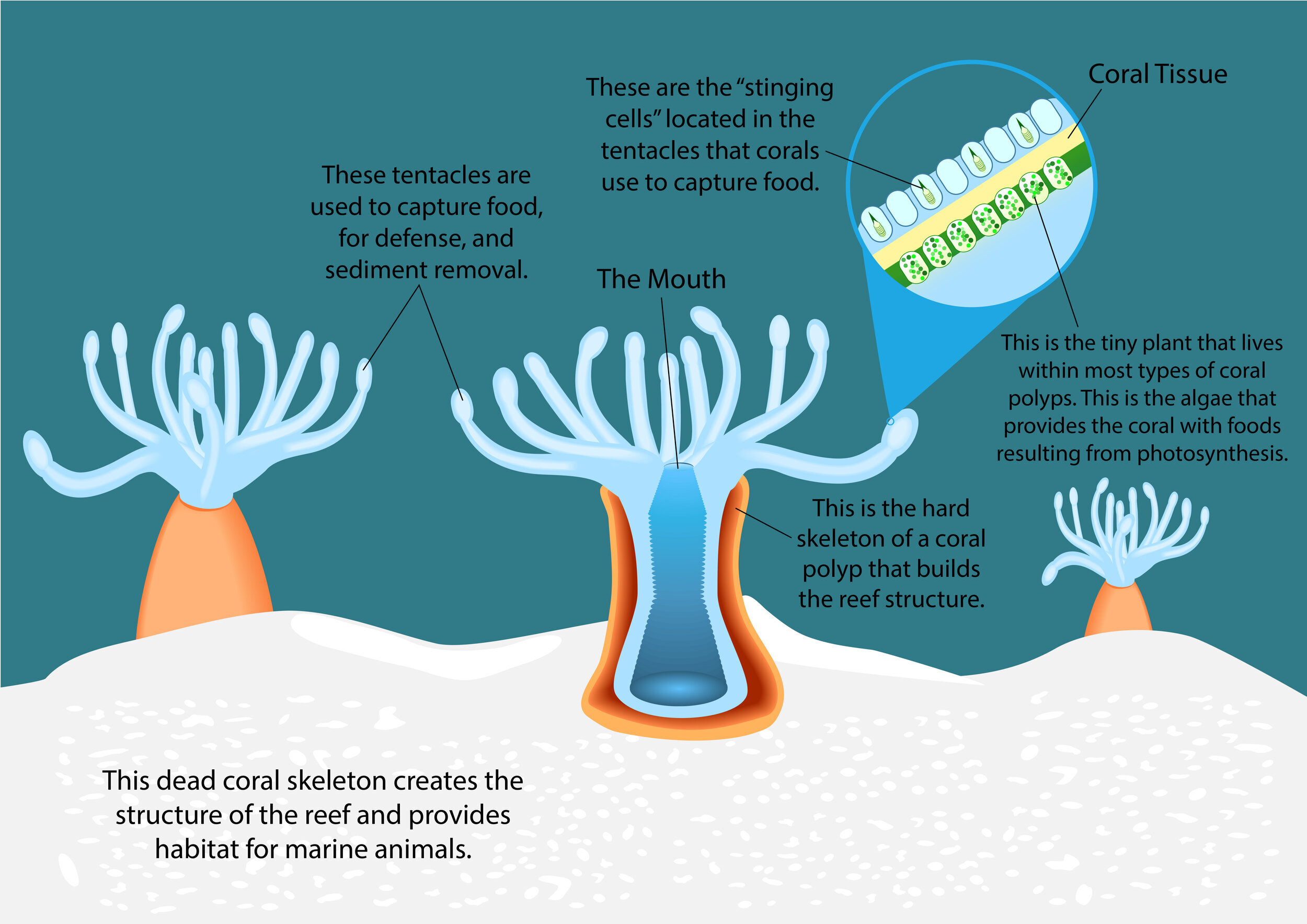

Here’s the deal: when corals die from a bleaching event (bleaching itself is not fatal), they have essentially starved to death. Corals are, weirdly enough, animals. They need to eat too! Corals and types of microscopic algae have evolved an incredibly interesting and unique symbiotic relationship with each other. It goes like this: the algae live inside coral cells and produces sugars and other carbs from photosynthesis. This food provides the coral animal the energy it needs to grow. In return the coral feeds with its sticky tentacles and gives back to the algae the nutrients it needs. This relationship essentially turns an animal, which can capture prey from the water, into a photosynthetic organism! Incredible.

Reef-building corals typically are very sensitive to heat, causing the precious symbiotic relationship to break down. When the algae die from heat stress, the coral may live … for a while… but if high temperatures continue for too long, even lingering bits of algae in the coral cells or water stream will be depleted and the coral will starve to death.

“We call corals the canary in the coal mine. They act as an early warning indicator of heat because they are one of the most thermally sensitive partnerships out there. When coral bleaching increases we see the early effects of warming oceans on the ecosystem.”

Why Do We Care?

When corals die, not only do we lose the beautiful underwater scenery our tourism-based economy relies upon, we also lose the structures that create habitats for reef fishes. The coral species most affected by bleaching are the major reef building corals. When the coral dies, the structure of the reef begins to crumble. Over time the reef may be reduced to rubble without healthy corals to replenish and reinforce the structure. To further complicate things, without herbivorous fish (the ones that eat algae, like parrotfish) on the reef, algae overgrows and reduces clean surface areas where baby corals can drift down out of the water stream and colonize.

“What we are seeing is a ratcheting down of the reefs, the overall recovery of a reef is slow and each event continues to push the reef’s health down. We aren’t seeing reefs take a hit and recover time and again, rather what we see is a long, slow decline.”

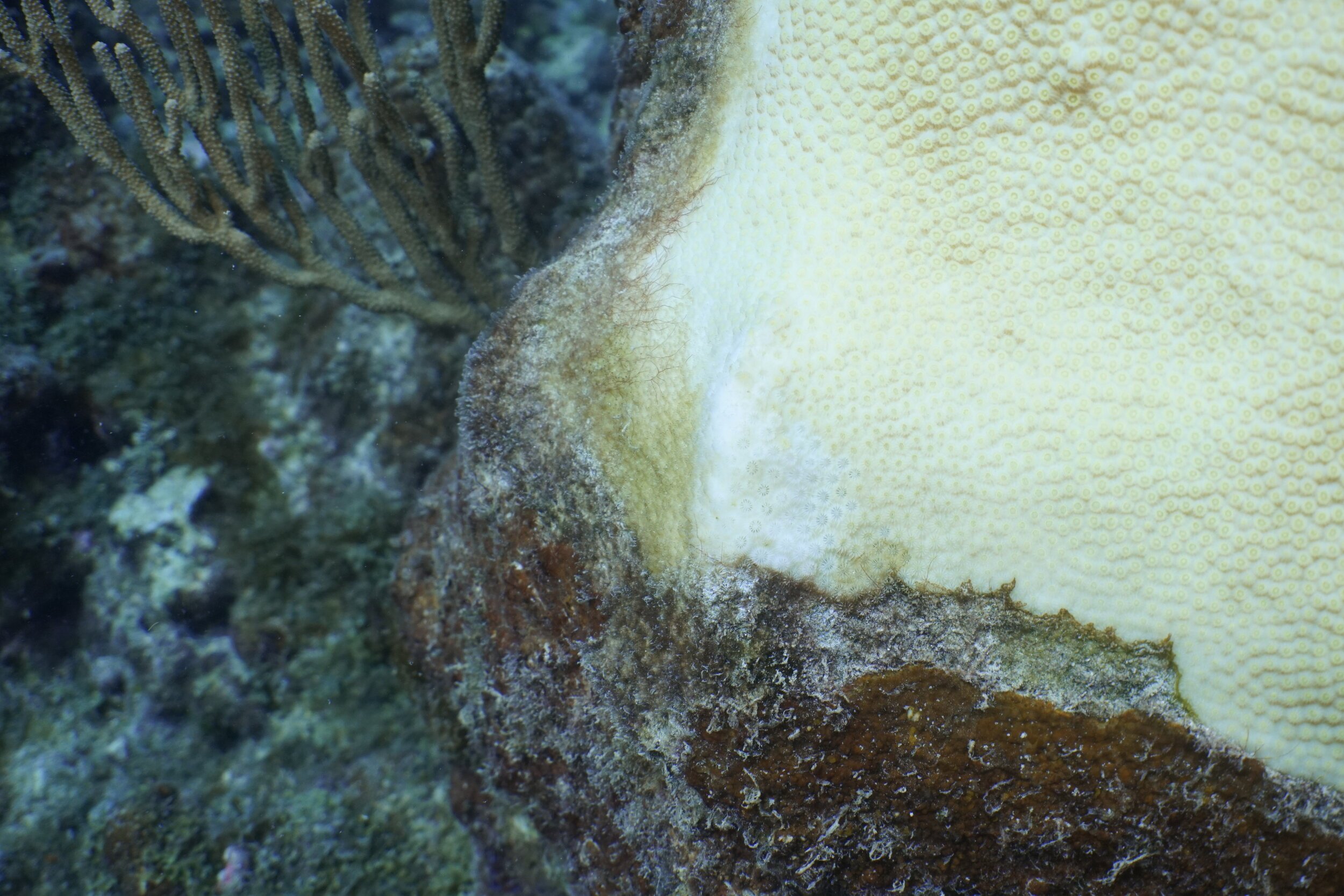

Coral scientists don’t expect a great deal of coral death from the 2019 bleaching event. “We just brushed the mortality threshold” says Dr. Smith, but corals in the territory are now greatly weakened because of the overly warm waters and are more susceptible to disease. What scientists witnessed during the 2005 event was that although some corals bleached and began to recover, they quickly became infected with coral diseases like white plague and black band.

The Flat Cay Reef

The Flat Cay Reef, located just south of the St. Thomas airport and close to UVI’s Center for Marine and Environmental Studies, is one of thirty-four reefs closely monitored through the Territorial Coral Reef Monitoring Program (TCRMP). Intently observed since 2005, Flat Cay is one of only three sites that survived and recovered from the bleaching event. It is sadly now the epicenter of the deadly Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) and has lost more corals in the last eleven months than it did in 2005. SCTLD is the one-two punch that our territory’s reefs simply did not need.

Is There Anything We Can Do?

What we can do is give corals a break! Two simple ways to give corals a chance to recover from these stresses are: eliminate runoff pollution and reduce our consumption of local herbivorous fish, like parrotfish. We can see from rainfall events that silt fences, for example, aren’t effective against runoff even when used correctly and in compliance to government regulations. The burden is on each of us to be responsible with where our trash goes and limit or eliminate single use plastics. And, importantly, we can demand legislation that is truly effective and supportive of our marine ecosystem.

We Are Down The Road.

There is no shining light here. We have arrived and where we find ourselves is….down the road. Coral reefs are in decline globally and scientists expect to see very little to no coral reefs by 2050. The solution to this awful reality is a political one, and one based upon societal will. The salvation of coral reefs and the continuation of the Virgin Islands’ tourist based livelihood depends upon a fundamental shift of our habits and priorities.

The US Virgin Islands has the opportunity to become a model for sustainability, if we have the will. The alternative is unthinkable.